"This year’s theme for World AIDS day is ‘Give the leadership to the communities,'" said Aboubacar Camara, a peer educator with the Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) HIV/AIDS project in Guinea. "The fight against HIV cannot exist without us, the community. We are eyewitnesses."

Camara not only works for MSF’s project, but lives with HIV himself, along with several other staff members and partners who have been providing medical care, psychosocial support, health education, and community outreach in Guinea. As we mark World AIDS Day on December 1, they share their own stories and eyewitness accounts on how HIV/AIDS care has evolved in the 20 years since MSF started its project in Guinea, and how to fight the stigma against people living with HIV.

Read more about MSF’s HIV/AIDS project in Guinea >>

"HIV may be in my blood, but the struggle against it is in my soul"

“I got my diagnosis on February 9, 2008. I was at university at the time. Since 2006, I had been constantly unwell. I went to see a doctor who advised I get tested for HIV. I hadn’t even heard of the disease. The doctor said it was a virus.

When my test results came through, I heard the doctors talking amongst themselves. They had stapled a piece of paper to my notes that said, ‘HIV positive.’ They thought I was illiterate. I looked at the paper and fell off my chair. It was beyond me. My big brother, who had come with me, said: ‘You just have to accept it; HIV doesn’t kill.’ The doctor prescribed me medication for three months.

After three months, I started to get better, and I went back to my studies. Once my prescription ran out, I didn’t renew it. I didn’t want the entire town to know my diagnosis, but then the illness got worse. I was living with my uncle at the time. I would normally have meals with the children, but I soon realized that they had begun to shun me. I was being stigmatized, discriminated against.

I attempted suicide twice. I had no information about the virus. It was the end of my world.

One day, I was listening to a show on the radio in which an activist, a peer educator at MSF, was talking about HIV and her diagnosis. She spoke the same language as I did. At the end of the segment, they gave out a phone number. I called it and the next day I met up with that same activist. She welcomed me and guided me. She said: 'If you accept your disease, you will be just like me. I live with HIV, but I’m not going to stop living.' She suggested I join a community-based organization and I agreed. I found comfort in that group. I even forgot that I was sick.

I heard that MSF was looking to hire someone to speak out publicly and tell their story as a peer educator. My family knew my diagnosis by then and I was no longer ashamed to share it with other people. I was available so I applied, and they hired me.

Since then, I have told my story publicly and MSF enables me to do that. There have even been documentaries made about me. That’s how I came up with some of my slogans, like: ‘HIV may be in my blood, but the struggle against it is in my soul.’

Now I also contribute to teaching people and demystifying misinformation about HIV in Guinea. I’ve spoken on television, in schools, and in public forums. Everywhere I can, I’ve spoken about my diagnosis. I’ve even participated in international conferences through MSF.

My role is to share my experiences with other sick people, to help them to accept their diagnosis, to help them live positively—like me.

Those of us who live with HIV are the best people to talk about it. I’ve also had experience of all the opportunistic infections that go with HIV. I also share my knowledge with other community-based organizations about rapid testing in the community.

In the past, there was no treatment, there was no counseling, there was no support available to people with the disease. Even the woman who handed out medications would mock the patients.

MSF has put in place a psychosocial care program. Some people say that treating HIV is 50 percent medical, 50 percent psychosocial. I’d say it’s more like 60/40 in favor of psychosocial care. If you take your medication with no information, you’ll just give up on the treatment. It’s the counselors who help you, who explain the side effects. They comfort you.

It’s also thanks to MSF that community-based organizations have been able to form. Being in a community-based organization is truly important. It’s another world. Even your family can’t offer what these organizations give you. I can say that the organization I am part of has given me a new life. Today, I’m healthy, even more so than some people who aren’t sick. And I eat way more. I have a family and children who are HIV-negative.

MSF is the only organization today caring for patients with advanced HIV in Guinea. The best-case scenario would be if there was a transfer of knowledge to the health authorities, to the community, and to community-based organizations. They are the ones who can keep the treatment going. And if the government accepted responsibility, things could get better.

This year’s theme for World AIDS day is ‘Give the leadership to the communities.’ The fight against HIV cannot exist without us, the community. We are eyewitnesses.

To this day, despite speaking freely, some people still don’t believe me. They have a hard time believing that someone like me, who has HIV, can speak so openly. But it’s what I know.

God wanted me to meet MSF. That’s why I want to keep up the fight against HIV until the day I die.”

"I have personally witnessed levels of stigma fall"

“I joined Conakry’s HIV project at its inception in 2003. At first, I would do at-home HIV testing. I had to stop traveling to patients’ homes by car because they were worried that their neighbors would discover they had potentially contracted the virus. I have personally witnessed levels of stigma fall in this country and watched knowledge about HIV grow amongst the population.”

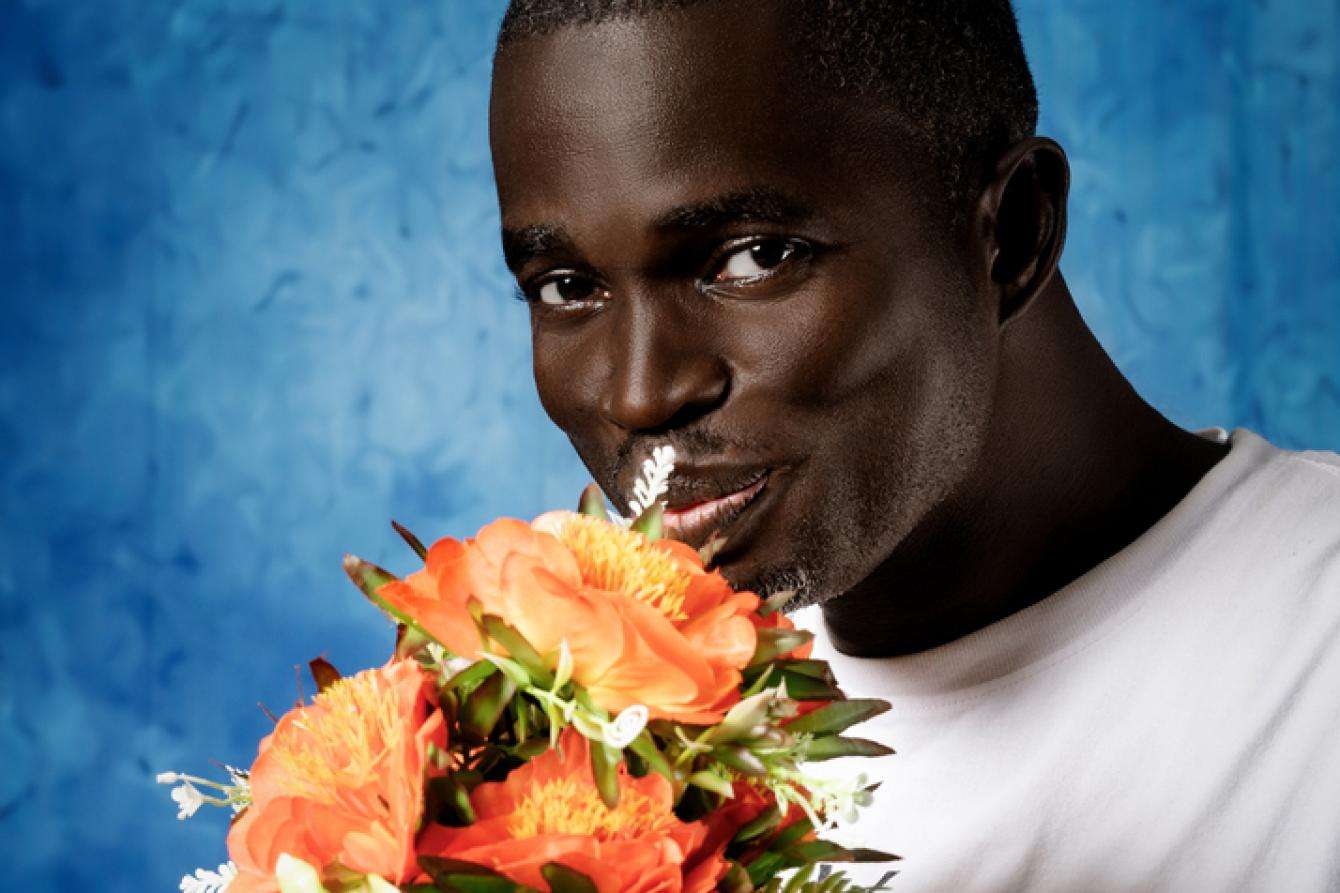

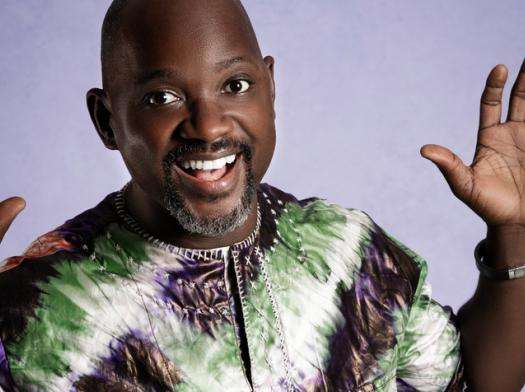

"I fight to defend the sick, give them hope and courage."

“I was a train conductor in 2005 when my boss called me into his office to fire me because I was off sick all the time. He suspected I had AIDS. He left the door and windows open when he made his announcement. He let me go after 24 years of service. I was livid.

A short time after, I saw an MSF commercial on television about HIV care. I went to get tested and when I got the results back, I was shocked: positive! At the time, HIV meant death. But I started my treatment and six months later I was healthy again.

The stigma against HIV patients is strong in Guinea. The neighborhood kids used to come to my house to watch TV. One eventually told me that the adults had discouraged them from visiting me because I had HIV. But I don’t condemn those who stigmatize; it’s the result of misinformation.

Some patients fear telling their families and communities. Some women don’t tell their partners about their diagnosis, for fear of being beaten. But those same husbands need to understand that marriage is for better or for worse, in sickness and in health. And sometimes, children abandon their parents.

I joined the Guinea Hope Foundation and in 2007 I volunteered to speak out openly. I fight to defend the sick, give them hope and courage. I help those who are afraid of HIV. I raise awareness and I am proud to lead the change. Today, stigma has decreased, and many things have changed.”

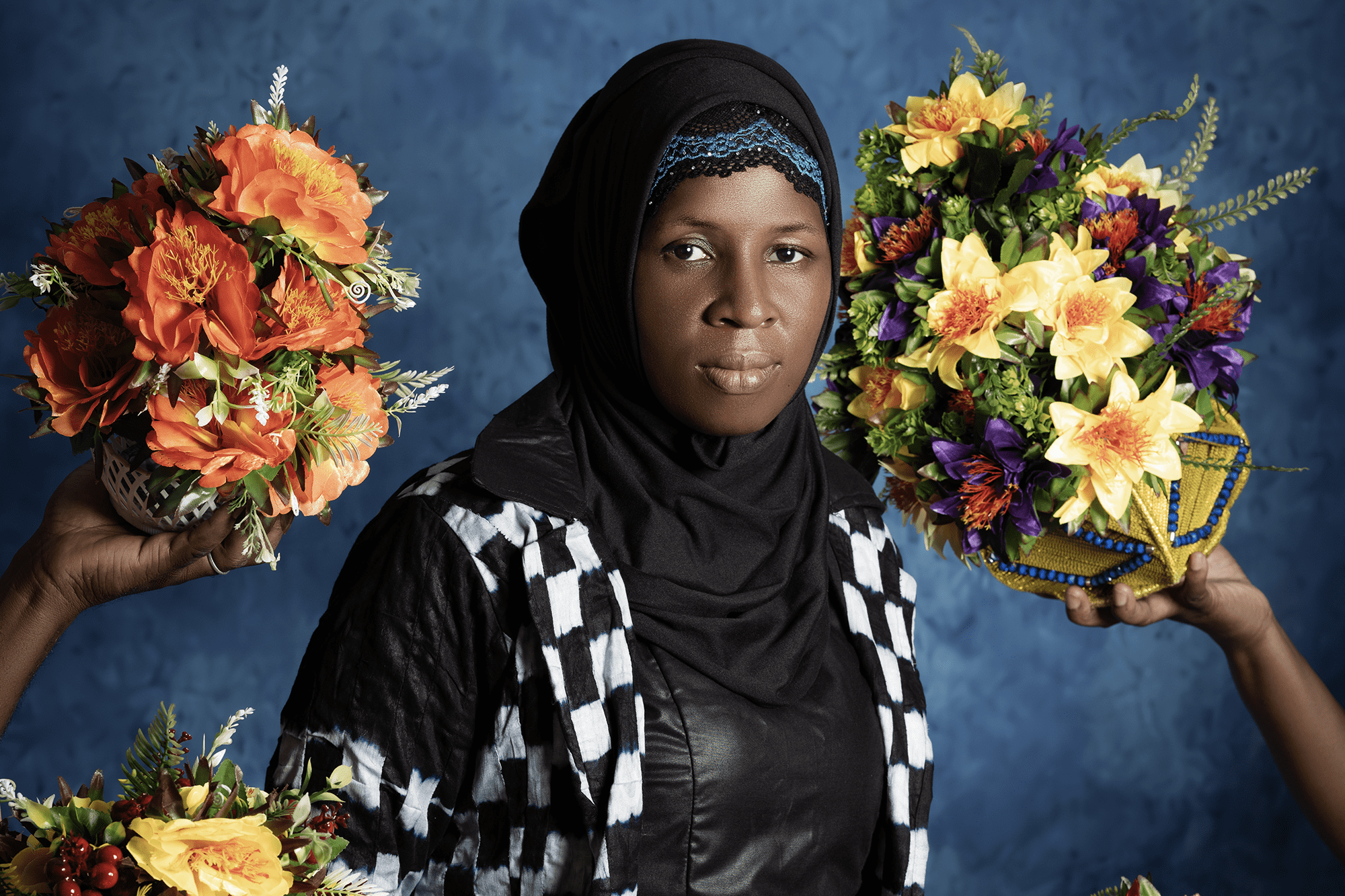

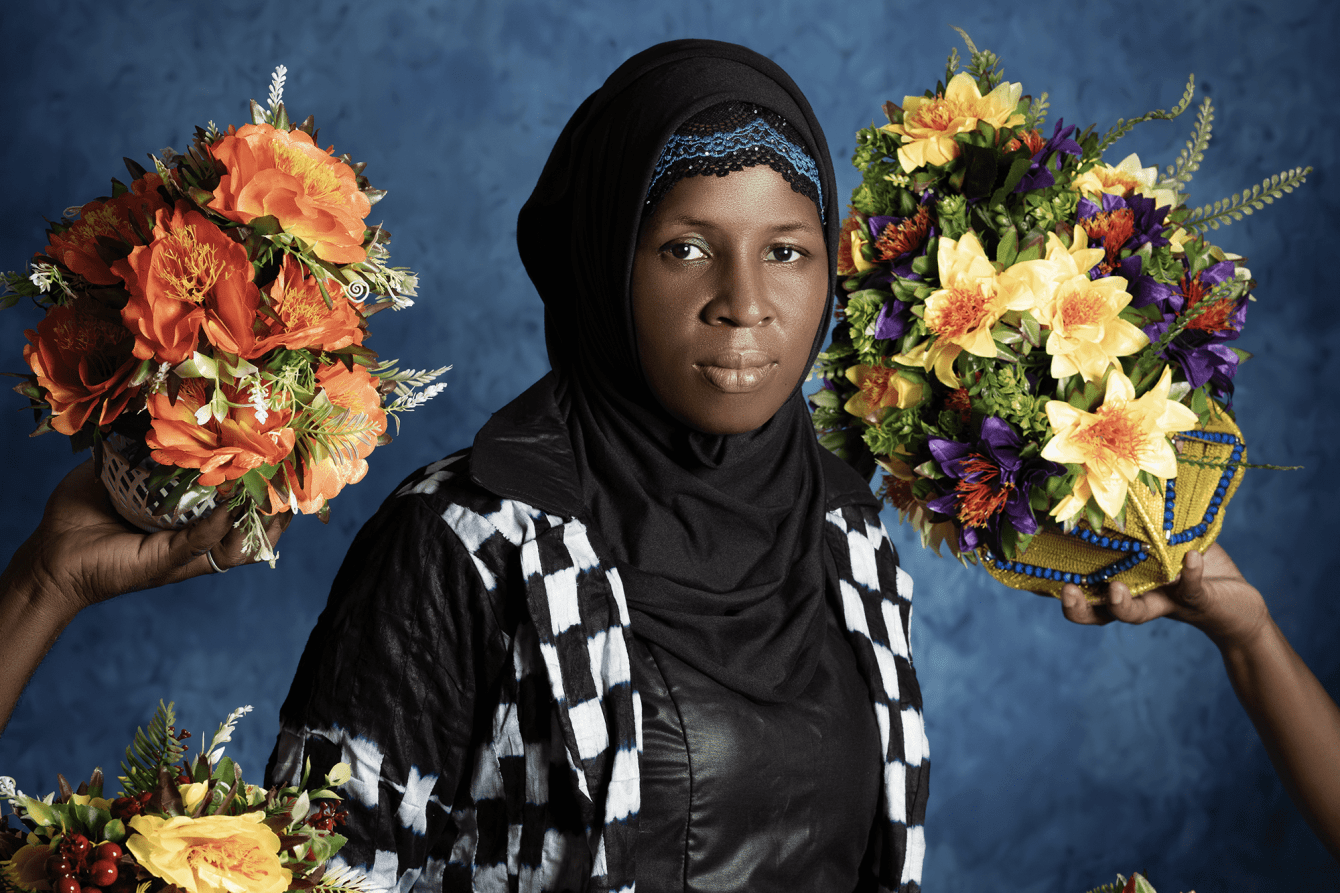

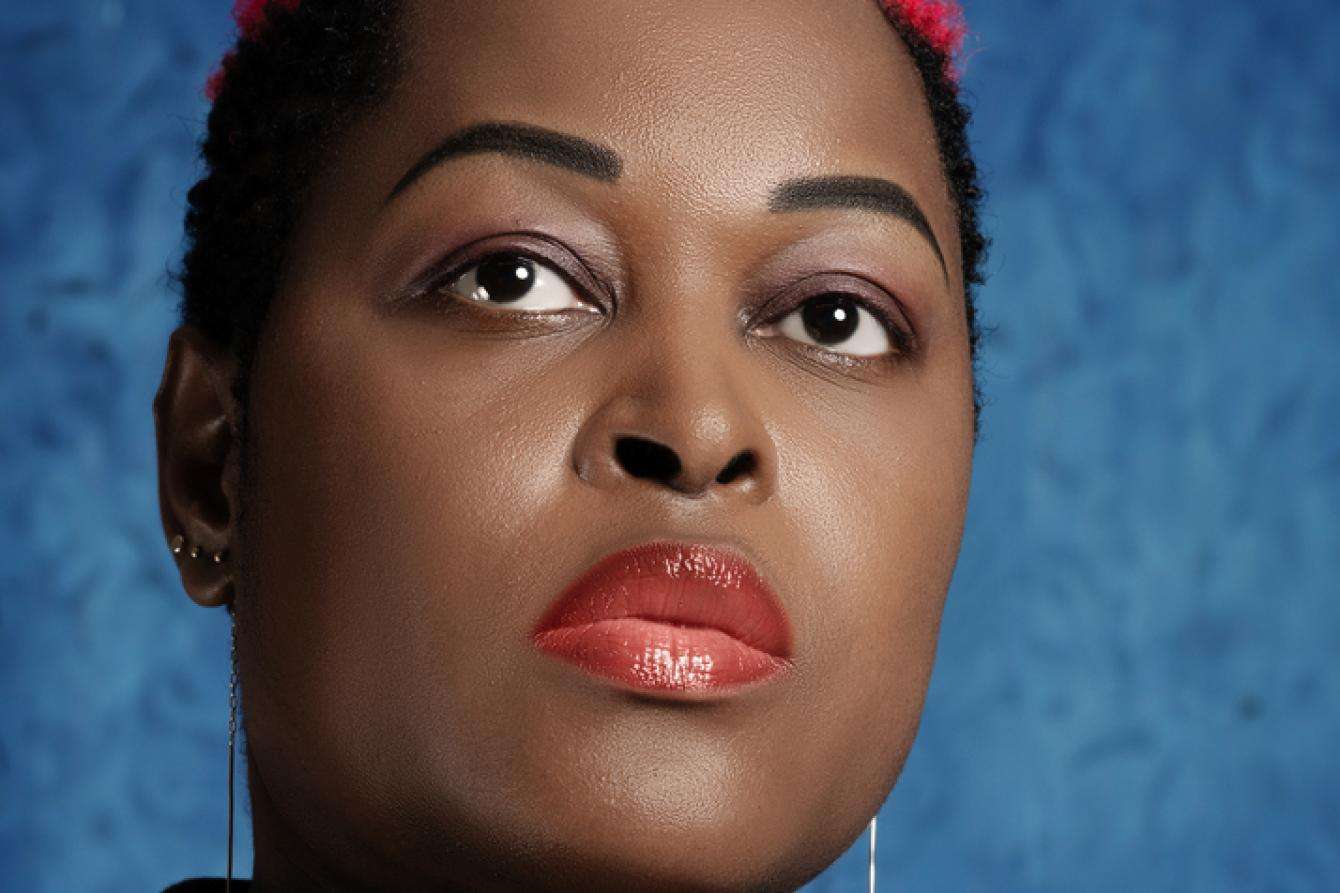

"My daughter knows I’m HIV-positive and has become my confidante."

“I was married at the age of 13 and my husband passed away sometime after. For 10 years, I was sick, but I didn’t know what was causing it. No one talked about HIV back then.

Later I remarried and discovered I was HIV-positive. That was it. I couldn’t shake it from my mind because, here, in Guinea, when you’ve got HIV, you’re seen as debauched and not taken seriously. But that wasn’t how I had lived my life. HIV was not meant for me. When my husband found out my diagnosis, he left me and my children.

I found MSF, I found a doctor, and I found community-based organizations that helped me get treatment. The support I received from MSF, my friends, and community-based organizations saved me from feeling traumatized. I found a job and I was able to care for my children.

Once again, I remarried and both my children were born HIV-negative, thanks to the prevention of mother-to-child transmission program. Today, they are 9 and 13. My daughter knows I’m HIV-positive and has become my confidante. I told her everything, to avoid the shock of her finding out the truth from someone else. She’s the one who reminds me to take my medication. I also told her to avoid touching my blood if I were to cut myself.

This year’s theme for World AIDS day is ‘Give the leadership to the communities.’ The fight against HIV cannot exist without us, the community. We are eyewitnesses.

Levels of stigma and discrimination are very high in Guinea and that’s why community-based organizations were created. I’ve been president of the Guinea Hope Foundation as well as president of the network for people affected by HIV/AIDS. These organizations help patients get psychosocial care. They also organize events, host radio shows, or find spaces for patients. Some organizations also manage places for the distribution of antiretrovirals, which are decentralized spaces created by MSF in 2020 and 2021 where patients can come and get their treatments easily.

Ignorance is still dominant here. People don’t know about the disease, and particularly about how it’s transmitted. Some people still believe you can only get infected through sexual intercourse, whereas it can be spread through cuts during certain ceremonies, in delivery rooms, or by way of sharp objects. But I am seeing the change from when I started raising awareness to today. People are now brave enough to say they have HIV. They are no longer mocked or rejected by the entire community like they used to be.

MSF supported me and never gave up on me. I realized I could do something with my life and give back to the community. Today I’m proud to help people, to bring them hope and self-esteem and help them find their path. I want to thank MSF for what it has done for the people of Guinea over the past two decades. I hope that state authorities will make MSF’s expertise their own, because MSF is the gold standard and the lead to follow.”

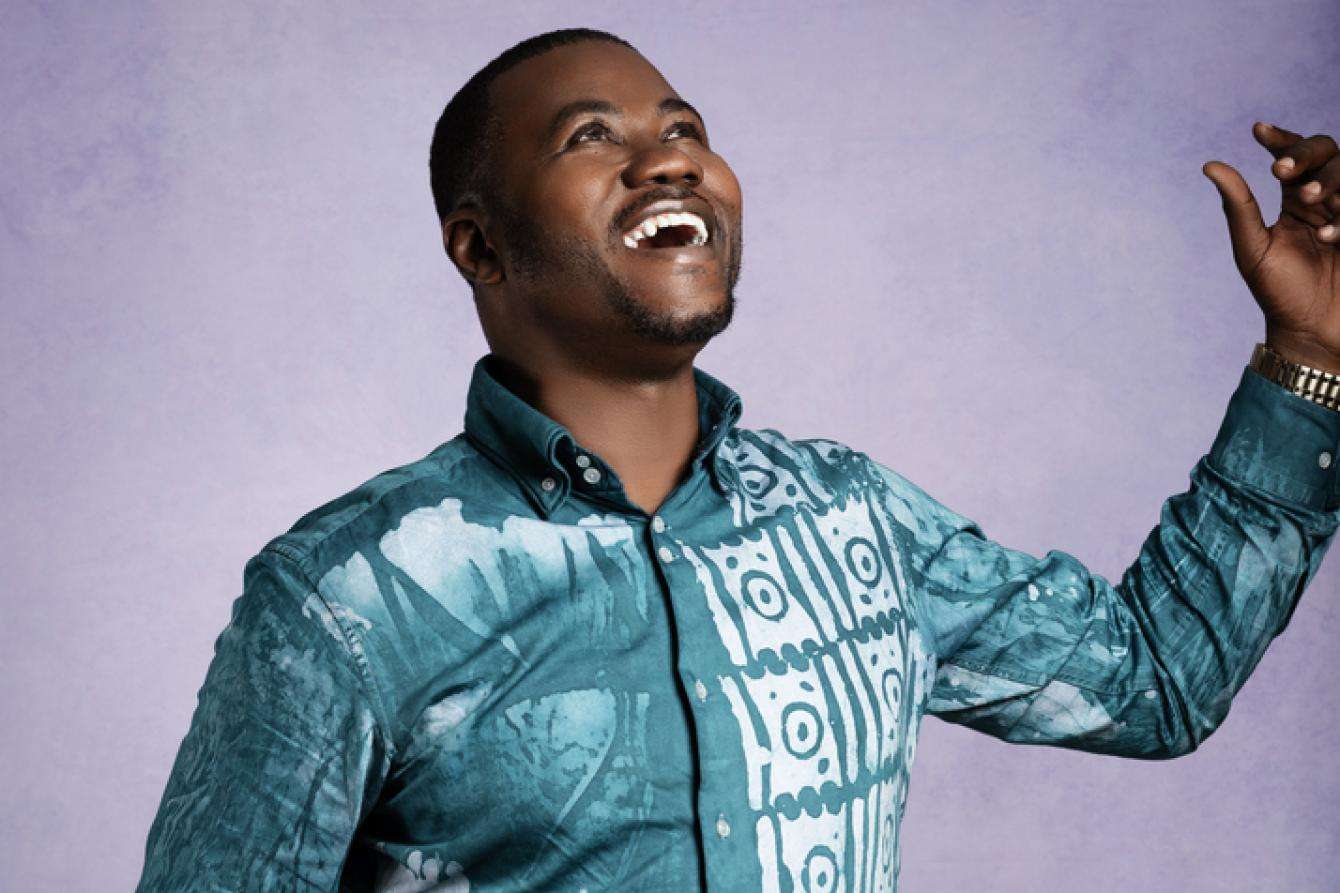

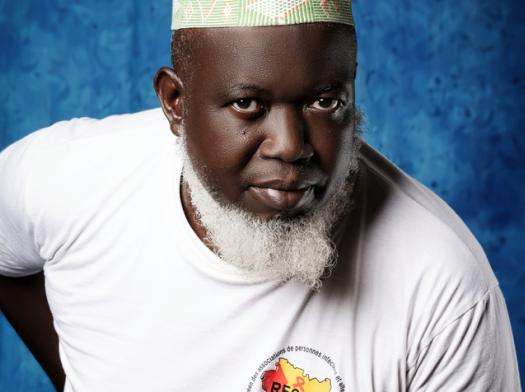

"Stigma is based on ignorance"

“I’ve been a health promoter since 2015. This role is the bridge between MSF and the community. We help raise awareness about HIV. We also raise awareness within the media. We explain that HIV isn’t like it used to be. Back then, it was deadly, but that’s no longer the case.

We also raise awareness of how HIV is and isn’t transmitted. Sharing a meal with someone who has HIV, drinking from the same cup, sharing the same bed, swapping clothes with them—that’s not how HIV is transmitted. Stigma is based on ignorance. When you raise awareness, ignorance decreases."

"If I had to choose between HIV and diabetes, I would choose HIV"

“I’ve held various positions with MSF since 1999. I had thyroid problems in 2003. MSF provided me with all the support I needed. I encourage my family, friends, and neighbors to get tested regularly and to donate blood. I try and raise awareness about HIV everywhere, even at the mosque.

Before, everybody would distance themselves from a person affected by HIV. Sick people would hide themselves away. Even I was afraid of it, but no longer. Today, with awareness campaigns, there are fewer issues.

We can’t choose our diseases, but if I had to choose between HIV and diabetes, I would choose HIV. As long as I keep taking my treatment, HIV is no longer a problem. HIV isn’t dangerous with treatment, although it is lifelong.”

From left: Néné Baldé Aïssatou, MSF midwife; Aïssata Diallo, MSF midwife; Bah Fatoumata Binda, MSF nurse. Guinea 2023 © Namsa Leuba

"Guinea was a ghost town when it came to HIV care 20 years ago."

“My name is Sékou Tidiane Touré, I coordinate community-building activities. I’ve been working for MSF for the past 17 years.

Guinea was a ghost town when it came to HIV care 20 years ago. You had to pay for treatment, and it was expensive. HIV was a taboo subject and having AIDS was considered a curse from God. At the time, the outpatient treatment center in Matam was known as the welcome center for les “Sidéens,” (a derogatory term for people living with HIV/AIDS). People hid their faces to come to their appointments and get their treatment. In 2003, there were few activities to raise awareness about HIV.

Things have changed drastically since MSF arrived in Guinea. Psychosocial care has been put into place, groups have been set up for people living with HIV, peer educators have started speaking out openly on television and the radio, awareness campaigns have increased. All these factors help patients stick to their treatment and lower their viral load, the indicator of how much virus is in their blood. These advances opened the door to putting into place strategies to schedule appointments at three or six-month intervals. It also allowed the creation of community distribution points for antiretrovirals by members of groups for people living with HIV. Treatment methods have also evolved: 20 years ago, patients had to take as many as 12 pills a day. Today, they only take one or two.

In 20 years, thousands of lives have been saved and hundreds of people have been properly trained. But despite all the efforts made to tackle HIV/AIDS over the past 20 years, people in Guinea still face difficulties accessing care. The funds allocated to the fight are insufficient; medical stock shortages occur regularly due to logistical issues distributing medications; not all HIV testing is free, outside MSF-supported health facilities; and finally, there are too few sites providing quality services.

On top of all this, discrimination is still prevalent, and some people are fearful of being seen at patient centers and of being ostracized, so they refuse to be open about their diagnosis.”

"Stigma was part of my daily life"

“I was 18 when I was married to a man I didn’t know. It was an arranged marriage, and he was 10 years older than me. I noticed a rash on his body. At the time, I had no idea what it was. Seborrheic dermatitis due to HIV was the furthest thing from my mind.

After four years of marriage, we separated. I got married again a decade later and that was when I found out that my first husband had died of complications related to HIV.

A short while after, I fell ill too. In the 2000s, in Guinea, doctors weren’t trained about HIV. None of them knew what I had. My older brother sent me to a clinic in England to get tested. When he found out my diagnosis, he didn’t tell me. But he told my husband and my family.

When I returned to my family’s home, they isolated me in my room and bought me new things so that I didn’t have to borrow anything of theirs. One day, I went back to my home and found out my husband had changed the locks. He told me to go back to my family, where they isolated me again. The disease continued to develop. I lost all my hair, I had dermatitis on my face, I lost weight.

My family sent me to see a doctor who told me that I was HIV-positive. My life flashed before my eyes: what I had been through, the behavior of my husband and my family.

My brother and family supported me financially so that I could get treatment. In the 2000s, some medications weren’t even available in Guinea and were hard to find. After many months of treatment, my condition improved and I recovered, so much so that my family, thinking I was cured, deemed my treatment no longer necessary. They no longer wanted to spend their money on it. Fortunately, my brother was able to continue to help me. He was afraid I would take my own life. It was largely thanks to MSF that treatments finally became free of charge in Guinea.

It was my doctor who told me about community-based organizations. I began volunteering for them, and since then, I have fought tirelessly so that people don’t have to experience what I’ve gone through.

In 2011, MSF suggested I join their team of peer educators, to speak out and fight against stigma. I also became a founding member of the national network of associations fighting HIV/AIDS in Guinea, the REGAP+. I organize testing, give results, support patients, and raise awareness. I’ve also received formal training and participated in international conferences. I am sometimes told that I know more about HIV than some doctors.

I also wrote a book, which has been translated into three languages, as well as made into a children’s book. If I had had this wealth of knowledge and information when I was younger, I probably would have had a different life.

Stigma was part of my daily life, in my neighborhood as much as within my family. It’s not HIV that kills, it’s stigma and misinformation. Levels of stigma were so sky high in Guinea. Today, thanks mainly to community-based organizations, stigma is decreasing."

“In 2013, I started volunteering with MSF. Today, I’m a health promoter and my main focuses are prevention and collecting blood, but I also raise awareness about sexual violence and help run training sessions for various groups. Until recently, I was also providing support for testing, but we’ve now transferred that knowledge to local groups. This is a real testament to the capacity-building MSF provides for its partners.”

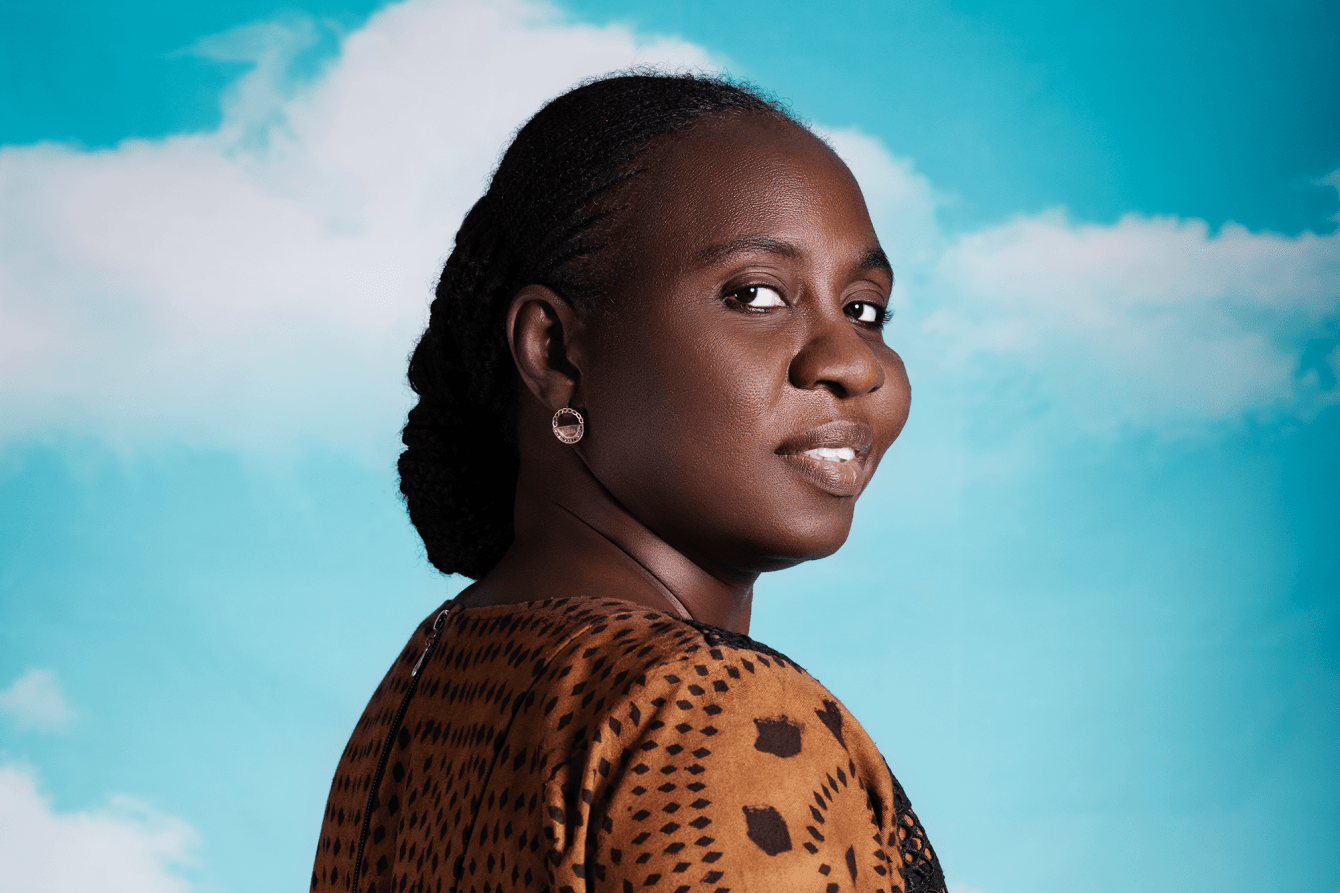

Sidibe Aïssatou. Guinea 2023 © Namsa Leuba

"MSF gave me advice on how to live and how to accept the illness."

“In 2002, my husband and I were watching TV when a commercial came on inviting people to get screened for HIV. My husband suggested we go. As we were newlyweds, I was proud, and we went. It turned out that I was HIV positive, and my husband was HIV negative. I thought I was going to die, that my life no longer had any purpose.

One year later, we got tested again, this time by MSF. The results were the same. The major difference was that MSF gave me advice on how to live and how to accept the illness. I decided I would live positively, and MSF supported me in doing that.

After a time, my husband told his parents that I had HIV. That was when the stigma began. As I didn’t have children, my in-laws wanted my husband to get married to a second wife. But the fact I was unable to have children wasn’t because of HIV. My husband didn’t leave me. We are still together, and he remains HIV-negative to this day.

I’ve volunteered for the organization Les amis de la santé. I’ve also been a member of other groups for people who are HIV-positive, I’ve taken part in training sessions, and I’ve been involved. In 2010, MSF recruited me as peer educator to talk to the media and to encourage people to get tested. Today, I help people get married and gain acceptance from their families despite their illness.

I think it’s important to talk about HIV openly to avoid stigmatization. For me, HIV is no different from diabetes or hypertension. If you follow your treatment regimen, you’ll live a long life. It isn’t written on our foreheads that we have HIV. People can live with it.”

"We were seen as know-it-alls"

“In 2010, when MSF started supporting the first three care centers in Conakry, there was no filing system for patients and prescriptions were renewed on pieces of paper. We immediately started patient files and implemented protocols. At the time, MSF was not well received by the Ministry of Health. We were seen as know-it-alls who came to stick our noses into their business. It took time to earn their trust.

In 2016, we participated in the Regional Technical Committee and we slowly became a strong supporting cast member. Since then, we’ve helped set up national guidelines for HIV care. Thanks to our donors, we also have the means to quickly put in place recommendations by WHO or the South African Medical Unit (SAMU). The national program to tackle HIV/AIDS can sometimes take years to implement these recommendations. In the past 20 years, we’ve also put in place activities that have gone on to be developed on a national scale.

MSF also provides technical know-how in HIV care. Namely, we’ve put in place appointments at six-month intervals, mainly for people living outside Conakry. This allows people to have more autonomy in managing their condition and maintaining patient retention. In the past, patients had to spend the equivalent of their monthly salary to come and replenish their medication every month.

We’ve also put in place points of distribution (PODIs) for antiretroviral medication managed by the members of community-based organizations. PODIs have allowed for a decentralized form of patient care within people’s communities, making it easier for patients to get treatment without having to travel long distances.

Across the eight health facilities that MSF supports, we treat one-quarter of the total number of people with HIV in Guinea. In 2022, MSF provided care for one-third of the women in the national prevention of mother-to-child transmission program.

One of our biggest challenges is medical stock shortages. Sometimes adults, and more worryingly, children, can spend weeks without receiving treatment. This can lead to the emergence of strains that are resistant to antiretrovirals.

Dr. Charles Tolno. Guinea 2023 © Namsa Leuba

"Thanks to MSF, I was able to receive training in advanced HIV"

“Thanks to MSF, I was able to receive training in advanced HIV in Democratic Republic of Congo. I also received training in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. With MSF’s support, we rarely have stock shortages of medications, unlike other health centers. We are able to test people for HIV and tuberculosis and provide COVID-19 tests and vaccinations. MSF has invested in expanding our facilities, renovating the maternity ward, drilling a new borehole for water, and implementing hygienic standards.”

Diallo Samba Sa. Guinea 2023 © Namsa Leuba

"I help them tell their families about their illness"

“I first heard about MSF when I was at university, and I immediately wanted to work for them. Today, I am an education counselor and I offer psychosocial counseling to patients. I help them tell their families about their illness. Sometimes we also discuss instances of the stigma and discrimination they’ve experienced. Often, patients are more at ease with the psychosocial support team than they are with doctors.”

Kolo Sovogui. Guinea 2023 © Namsa Leuba

"As a doctor, I see patients who arrive in an advanced stage of HIV every week"

“HIV remains a problem in Guinea. Despite MSF’s best efforts, and that of their partners, many Guineans still aren’t diagnosed with HIV and don’t have access to treatment. Furthermore, following the viral load remains difficult.

Numerous factors come into play, including the fact that people with HIV hide their status from their families. This is due to fear of rejection, isolation, and being stigmatized and discriminated against. Another issue today is regular stock shortages of ART, antituberculosis medication, and HIV lab consumables and reagents to determine viral load, as well as the cost of treating opportunistic infections.

As a doctor, I see patients who arrive in an advanced stage of HIV every week, particularly at tertiary care clinic at the Unité de Soins, Formation et Recherche Donka, which receives support from MSF.

Today, some 16,500 HIV patients benefit from free medical quality preventative, curative health care and psychosocial support in Conakry, MSF’s intervention zone.

A final challenge of note that remains helping the ministry reach the UNAIDS 95-95-95 objective: to diagnose 95 percent of all HIV-positive individuals, provide antiretroviral therapy for 95 percent of those diagnosed, and achieve viral suppression for 95 percent of those treated by 2030. Where MSF’s active line is concerned, we have met the second objective at 99.8 percent and 90 percent of our patients on ART have an undetectable viral load. However, according to UNAIDS, on the national scale: 68 percent of HIV+ people know their status; 95 percent of those are on ART, and the data on viral load suppression is unavailable."