A malaria surge in Haut-Uélé Province, in northeastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), has seen 1,600 children admitted with severe malaria and more than 40,000 people treated for the disease by a Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) emergency team in the past seven weeks. MSF worked alongside local staff in health facilities in the Pawa and Boma-Mangbetu areas.

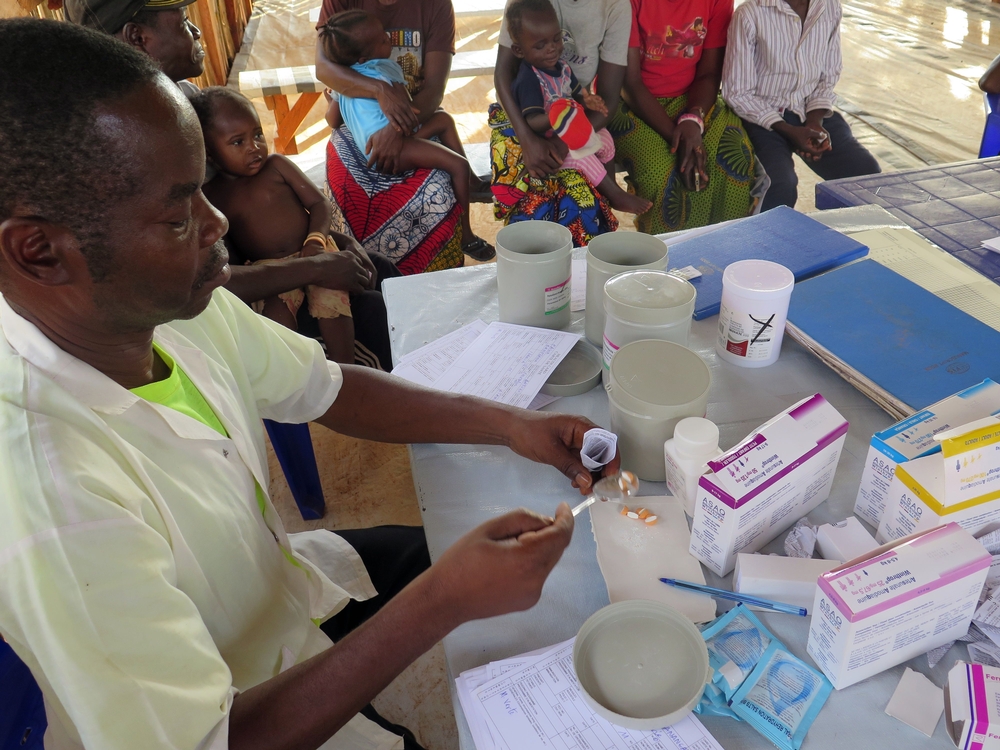

“With such a huge influx of patients, local health facilities had run short of drugs to treat malaria,” says Stéphane Reynier de Montlaux, MSF emergency coordinator in Pawa. “Since the MSF team arrived on May 9, we have made sure that rapid malaria tests and antimalarial treatment are available at 32 health centers across the region in order to treat cases of simple malaria and prevent complications. However, getting supplies of drugs into the region continues to be a challenge and our logistical support is still highly needed.”

Addressing the Needs

MSF’s emergency team also set up treatment and intensive care units within the main hospitals in both Pawa and Boma-Mangbetu, providing additional doctors and nurses; as well as drugs and vital equipment, including a 24-hour supply of electricity, beds, mattresses, and medical supplies.

The situation is severe, as 95 percent of the patients tested positive for malaria. More than four in five of those admitted to the hospital with complicated malaria are children under the age of 12, who are particularly vulnerable to the disease.

“Many of the young patients arrive at the hospital in a serious condition,” says Reynier de Montlaux. “Many have severe anemia and need blood transfusions, but there are not enough blood donors to supply the hospitals' blood banks.”

“We are also seeing a significant number of cases of severe malnutrition amongst the patients, so we have also had to treat malnutrition and train local health staff in how to deal with it,” says Reynier de Montlaux. Malnutrition weakens children’s immune systems, making them more susceptible to other deadly diseases, including malaria.

Stabilizing Cases

In the health center in Babonde, midway between Pawa and Boma-Mangbetu, MSF set up a stabilization unit for people who are unable to reach a hospital. In some remote areas, people live more than 30 miles from the nearest hospital, along roads that may be impassable, while the cost of transport is often unaffordable.

MSF aims to make improvements to the way in which patients with severe malaria are referred to hospitals, as well as improve the skills of local health care staff, who are on the frontline of patient care. The team is also working on improving community awareness of malaria, so that people with symptoms receive treatment as quickly as possible.

Multiple Surges

Other health areas have also raised the alarm over malaria. After an increase in malaria cases was seen in the Dingila region of Bas-Uélé Province, an MSF team was sent to the area. Although the situation has stabilized, the number of cases around Dingila remains high. Local people are also experiencing difficulties accessing treatment, mainly because health facilities have run out of drugs. The MSF team is planning to support the health system in taking care of severe cases, especially in rural areas.

The current surge in malaria in Haut and Bas Uélé is almost unprecedented. “We have only ever encountered a similar situation once before,” says Reynier de Montlaux. “Between June and October 2012, MSF treated more than 60,000 children in the areas of Ganga-Dingila, Pawa, Poko, and Boma-Mangbetu. This year, we responded earlier and have worked closely with the authorities to curb the outbreak. But while the number of cases appears to be decreasing in some health centers, this is not the case everywhere and it is far too early to let our guard down as the malaria peak season is beginning.”