On the fifth anniversary of the brutal conflict in Syria, a Syrian doctor working in a suburb of Damascus reflects on fear, exhaustion, and uncertainty.

I graduated in 1995 and opened up a clinic on October 10, 1995. In 2001, I became specialized in urology. There were around 40,000 residents in the area before "the events" [the Syrian uprising of 2011]. Now, the population here, including the displaced, is currently around 15,000 individuals.

I work in mainly two clinics. One experienced numerous strikes, and it was closed down and we transferred to the second makeshift clinic, which was also hit a lot. The last strike against this second clinic was on September 28, 2015. Four people were killed, including a friend of mine who was the director. It was very violent, that strike.

We have rebuilt the clinic as we usually do. We’re still lacking the physiotherapy room and the outpatient department is currently just a big room divided between genders, yet the clinic still provides all types of medical services, starting from emergencies, outpatient rooms, surgeries, [and] laboratories to X-rays [and] physiotherapy. It is an essential clinic for the Ghouta area.

Patients are afraid to come because of the strikes. They always tell me not to take them to the clinics; they would rather go to centers (smaller health posts) because clinics and hospitals in the area are more likely to be targeted.

One of the Patients Might be a Family Member

You see all types of casualties. Just today, as patients were coming in, they were telling me how much I’ve grown in these times; I responded that this is because of the injuries I’ve seen. Because you see patients who lost a leg, their head decapitated, their hand cut off.

In the future, the doctors in areas like Ghouta will be considered the most famous in the world because of the extraordinary things they had to do. Because of the limited number of doctors in East Ghouta, and especially in any of the besieged areas, any doctor remaining is forced to play multiple roles. I am a urologist and a gynecologist, I’ve done more than 200 C-section surgeries, I’ve done general surgeries, and I’m a pediatrician. I have to do everything.

The hardest moment we face is the fact that when patients are brought in, you have this strange sensation that one of the patients might be a family member. More than that, you see a patient, who you’ve only spoken to five or ten minutes earlier, brought in without a face or head. This is truly the hardest moment for me.

The Worst of Times

It is a bit better today, but the years of 2013–2015 were the worst of times. The situation regarding resources has been improving for the last four months because of the easing of the blockade, and aid arrived around 10 days ago with about 53 kilos of goods allocated for each family. The breakdown is like so: 15 kilos flour, 10 kilos rice, 4 kilos bulgur, 5 kilos sugar, 6 kilos chickpeas, and a kilo of spaghetti. There were also some medical supplies. This was brought in by the Syrian Red Crescent.

Before this convoy a kilo of sugar was 1,000 lira [Syrian pounds, about 5.3 USD total]. A kilo of bread reached up to 1,000–1,200 liras [5.3–6.35 USD]. Now, bread, for example, is priced at 300-350 liras [1.6–1.85 USD]. There’s food, there’s fruit! Fruit! Last year, I remember, I had bought four oranges for 3,000 liras [15.9 USD] for my children.

There are still limited medical supplies, but not as bad as before. You can say that we’ve currently reserved about 50–60 percent of our needed medical supplies. Two years ago, in comparison, medicine was 2,000–2,500 liras, [10.6–13.25 USD] now it is 900 liras [1.77 USD].

They Simply Want the Violence to Stop

Yet in the context of this war, [things are] still very bad. There are always planes; always injuries, casualties, dead.

Everyone is fatigued with the fear and death. People all wanted freedom, wanted the revolution to persist, but now they have reached a point where they simply want the violence to stop. Everyday someone says goodbye to their relative. Every day there was fear. I was one of the few people who would go out in my car to other areas to work in makeshift clinics. Every time I go out, I would pray, because I’m not sure I’ll return to my children. Yet for the past five or six days now, I’m not afraid to go out. This is the first time, in three years, that I feel safe and unafraid from a strike.

Still, we hear the sounds of gunfire. Nearby, there are battles raging and getting closer. The cessation of violence actually does not exist, but it did decrease violence. You can say the level of violence is around 15 to 20 percent from what it was. People are still afraid of what will happen after the cessation of violence ends, especially given that a day before the cessation of violence came into effect, we had around 50 strikes onto Ghouta. It was as if the people bombing us wanted to say a brief goodbye. We are worried that once the cessation ends, the response is going to be harsh.

|

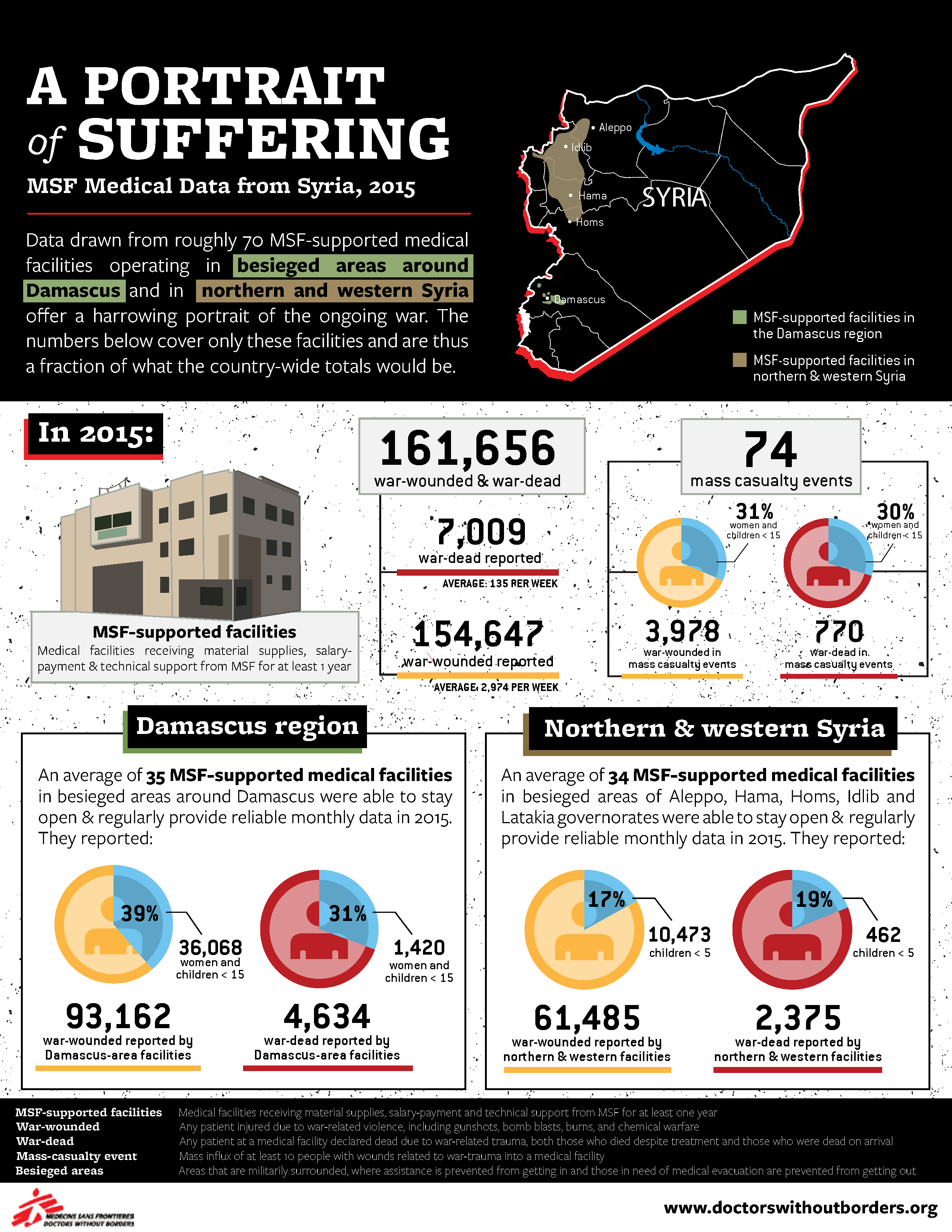

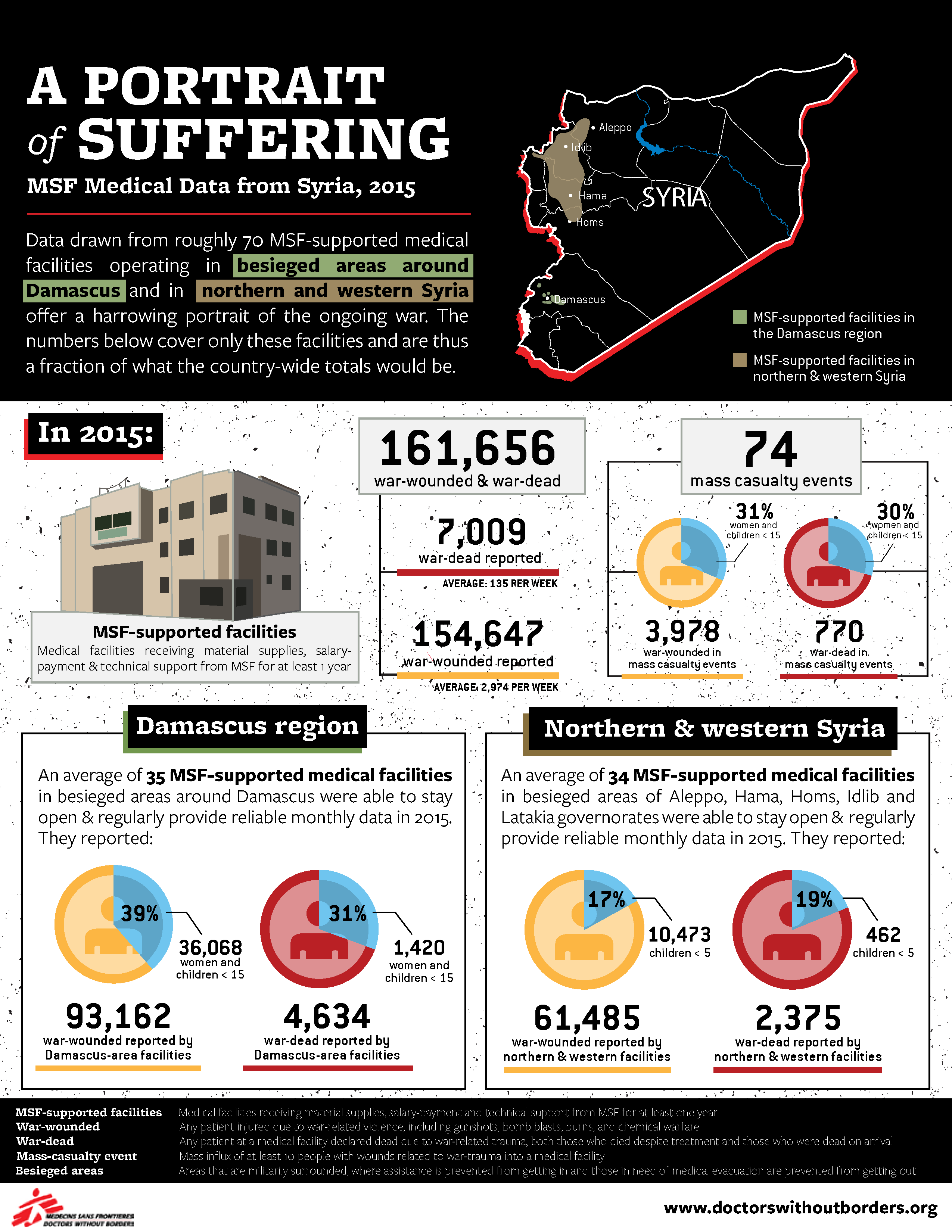

Civilians are under relentless attack in Syria’s five-year-old conflict, with 1.9 million people under siege, borders closed to refugees, and rampant bombings of medical facilities and heavily populated areas. MSF calls on permanent UN Security Council member states involved in the Syrian conflict—specifically France, Russia, the UK, and the US—to ensure that they and their allies abide by the resolutions they have passed to halt the carnage. In a report issued on February 18, MSF details the toll of the conflict on civilians, based on data from 70 hospitals and clinics that MSF supports in northwestern, western, and central Syria. In all, 154,647 war-wounded people and 7,009 war-dead were documented in the facilities in 2015, with women and children representing 30 to 40 percent of the victims. Read More. |